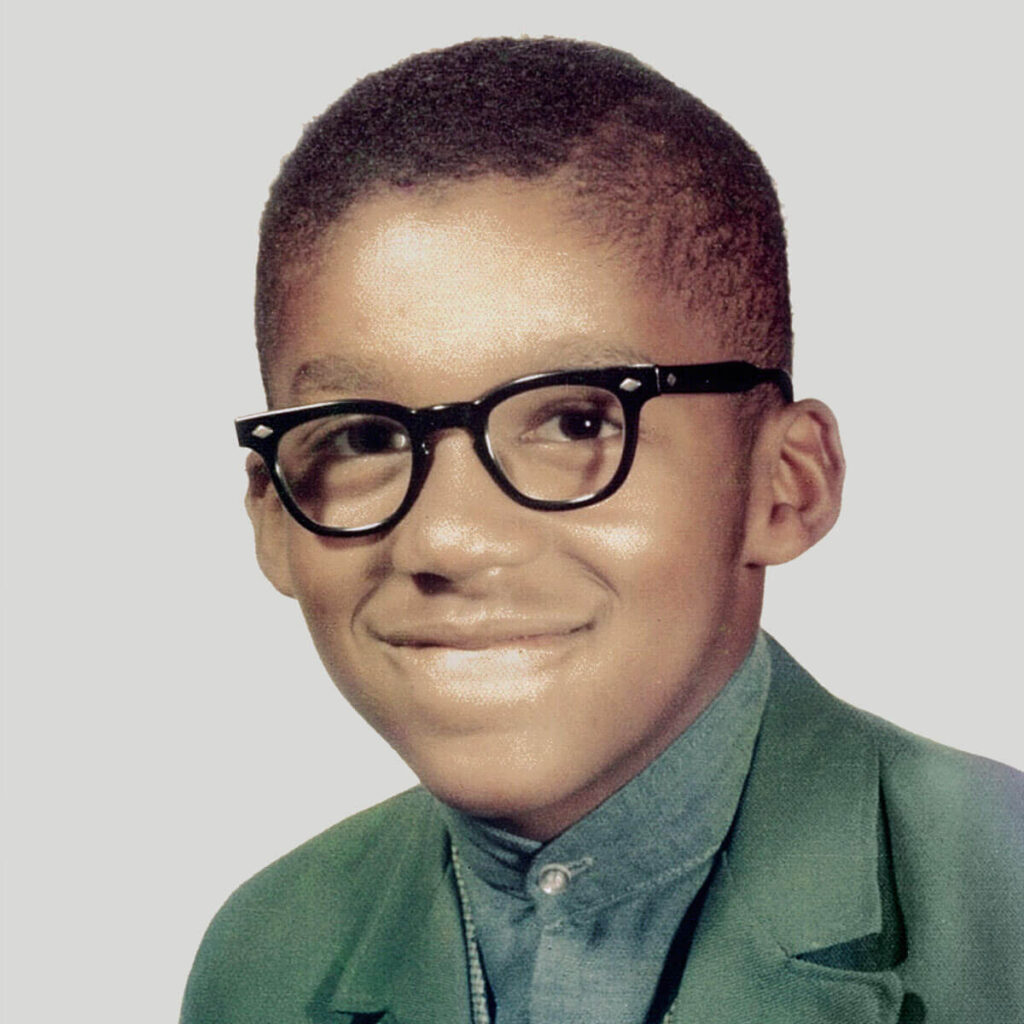

As the crow flies, Milton, Delaware, where Bryan Stevenson grew up, is 916 miles from Montgomery, Alabama.

Two generations ago, when Jim Crow laws mandated segregation across the south, the shadow of apartheid extended all the way to Sussex County, where Stevenson remembers black children standing in line behind a health center, waiting for their polio vaccines after white children received theirs. He attended a segregated school in first grade, before the 1964 Civil Rights Act barred racial discrimination. Even after his school was desegregated, white kids and black kids played separately.

“Sussex County was, in every way, southern,” he recalls.

His early years in Milton were a precursor of sorts for life in Montgomery, where Stevenson has worked for more than 30 years, representing prisoners on Alabama’s crowded death row. He is founder of the Equal Justice Initiative, which stands on ground where enslaved people were once held in chains awaiting auction. His best-selling book, “Just Mercy,” was made into a movie in 2019 in which Stevenson is played by Michael B. Jordan. And he’s the inspiration for the Bryan Allen Stevenson School of Excellence, a Georgetown-based public charter school slated to open this fall.

“I love going back home. Delaware is a beautiful state and has an enormous opportunity to be a leader nationally.”

— Bryan Stevenson

Stevenson comes home often and is heartened by Delaware’s progress in ensuring justice for all, such as the Delaware Bar and Bench Diversity Project, which calls for more lawyers and judges of color, especially in Sussex County. When he looks to the future, he thinks the First State has the potential to set a standard for a diverse, equitable and inclusive society.

“I love going back home. Delaware is a beautiful state and has an enormous opportunity to be a leader nationally,” he says.

Stevenson has always been intrigued by history and the lessons the past imparts to those who are willing to listen. He is heartened that Sen. Chris Coons and Rep. Lisa Blunt Rochester supported the placement of a historical marker in Greenbank Park in New Castle County in 2019 commemorating the 1903 lynching of George White, who was dragged from jail and burned by an angry mob after he was accused of murdering a white girl.

“The only way that we can learn from our past is by confronting it,” Blunt Rochester said at the dedication. “It is my hope that this historical marker will serve as a solemn reminder of this vile incident for generations of Delawareans to come and that our community will use this as a catalyst to fight racism and bigotry wherever they see it.”

In 2022, Coons reiterated that sentiment when he introduced Stevenson as the keynote speaker at the U.S. Senate’s 70th annual Prayer Breakfast. “As Bryan has said, our nation’s history of racial injustice casts a shadow that can’t be lifted until we shine the light of truth on the destructive violence that shaped our nation that traumatized people of color and compromised our commitment to the rule of law and to equal justice,” Coons said.

At 63, Stevenson also reflects on his personal history. His father, Howard Sr., was a lab tech in Dover. His mother was an equal opportunity officer at the Air Base there. The family was rooted in faith and in music, attending Prospect African Methodist Episcopal Church in Georgetown, where Stevenson played piano and sang in the choir. His sister, Christy Taylor, became a music teacher.

He notes that his father grew up in a time when the high school was segregated, meaning black students had to travel outside Sussex County to attend classes.

“When I was a child, very few black adults had a high school education. I was part of the first generation to attend an integrated high school,” he says.

Stevenson was a student at Cape Henlopen High School when the team won the state basketball championship. It was one of the first cracks in long-standing racial barriers.

“Committing to diversity created success,” he says. “The whole community was engaged and excited about our team. I’d like to see that kind of enthusiasm for diversity in areas beyond sports and entertainment, like business and education.”

After high school, Stevenson earned a philosophy degree at Eastern University, a Baptist-affiliated school on Philadelphia’s Main Line. He went on to Harvard Law School, “the first place I ever met a lawyer.”

He wound up in Alabama to provide a guaranteed defense for inmates sentenced to death, as it was the only state that did not provide legal assistance to people on death row. Alabama also has the highest per capita rate of death penalty sentencing.

“Just Mercy” focuses on the case of Walter McMillian, wrongly convicted and sentenced to death for the murder of a dry-cleaning clerk. After his release, McMillian took a lumbering job, but his health was broken by the trauma of years behind bars. Stevenson brought him to live at his house and the two men traveled together advocating for social justice.

“He remained my friend and brother for the rest of his life,” Stevenson says.

His work has resulted in more than 140 prisoners on death row having their sentences reversed or being released from prison. He’s won landmark cases before the U.S. Supreme Court, including a 2019 ruling protecting prisoners with dementia from execution and a 2012 ruling that banned mandatory life sentences without parole for offenders 17 and younger.

Stevenson’s passion for history as a learning tool led to the creation of two acclaimed cultural sites which opened in 2018 in Montgomery. The Legacy Museum and the National Memorial for Peace and Justice chronicle the legacy of slavery, lynching and racial segregation, and their connection to contemporary issues of racial bias.

Despite his accolades and accomplishments, he lives simply. He is a bachelor and has never taken a drink. Among his rare indulgences is a slice of Grotto Pizza when he comes home to visit family.

The Stevenson charter school, which will be located on Delaware Tech’s Sussex County campus, will be tuition-free and focus on public service. He became acquainted with the co-founder, Chantalle Ashford, through his cousin Teresa Berry.

“I wanted to design the school I would have liked to attend as a student and where I would want to work as an educator. I’m excited to lead a building where care and learning are at the center of what we do,” Ashford said in a statement.

Although Stevenson is not formally involved with the curriculum, he supports the school’s culture of compassion and equity.

“I am honored that they are committing to doing this,” he says.

Five Things Bryan Loves About Coming Home to Delaware

➊ Spending time with family, especially his sister Christy Taylor.

➋ His favorite beach is the north end of Rehoboth Beach.

➌ “A visit to Delaware is not complete without Grotto Pizza,” he says.

➍ Shopping at Tanger Outlets. “When the outlets came, it was a big deal for people in Sussex County,” he says. “People in Alabama are stunned when I tell them there’s no sales tax.”

➎ Lunch at Pizza Villa in Rehoboth Beach. “It’s the best Philly cheesesteak ever.”